In this new space, we’ll reflect on what we consider to be the most relevant album of the week. In this installment: Cowboy Carter by Beyoncé.

Anything Beyoncé is involved in is synonymous with immediate mass attention, even if it’s an album based on the American mainstream genre that most strictly adheres to its own sonic tradition: Country.

So strict and conservative are the codes of Country music regarding its musicality and its discourse that, perhaps, its last great revolution was more than 40 years ago, when Dolly Parton broke the paradigms of the genre as a narrator of American life far from the cities to turn it into a platform for Pop stories about love and broken hearts.

Although the industry has recently tried to lighten it up to reach new generations through highly publicized projects (Taylor Swift’s first phase, no less) or through a rock/pop filter (just listen to Lady Antebellum or Blake Shelton), in essence it’s still closer to 1960 than 2024.

This is where Beyoncé and her most recent album, Cowboy Carter, come in. It’s the second album in a trilogy whose rules and guidelines aren’t entirely clear, but which has a clear objective: the vindication of the African-American community in the history of musical movements generally associated with whites.

This is what he did in Renaissance (2022) and the chronological review of nightclub culture, and this is what he seems to attempt in Cowboy Carter , not only with regard to the study of Country as a black genre; but also from its intimacy with Soul, Folk, Blues and Gospel.

With the statement of intent in place, this album must be approached in three phases: its conceptualization, its execution, and the bridge between the two. In other words: what it claims to be, what it seeks to be, and what it ultimately becomes, especially because the key to its nuances lies in the fabric of that structure.

What it claims to be

According to Beyoncé herself, the desire to make this album arose almost eight years ago, when she attended the Country Music Association Awards to perform one of the many hits from her album Lemonade (2016): “Daddy Issues”, a Country/Folk track that was very well received by the industry but that the universe of said genre felt like an opportunistic intrusion into a field that did not correspond to it.

Needless to say, this position sought to conceal a racist stance, especially in the year in which Trump had just risen to power, precisely thanks to that kind of messaging.

The rejection was so obvious that Beyoncé sensed it, and from then on, a desire for revenge began to develop. While developing other productions, Queen B says she embarked on a personal journey that lasted more than five years, exploring the history of African-American music, particularly country, folk, blues, soul, and gospel.

This process is the seed of Cowboy Carter , which also “comes at a very fortunate time” for pop culture and consumer trends given the rise of the cowboy aesthetic, something that designer Raf Simons predicted in 2017 in his first collection for Calvin Klein and that Pharrell Williams has taken to its maximum expression at the beginning of this year with his summer catwalk for Louis Vuitton.

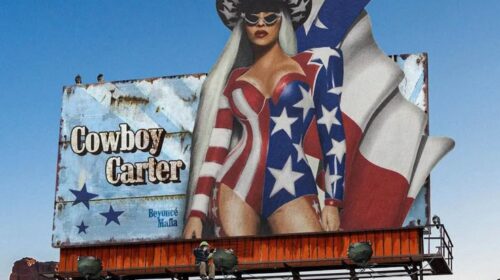

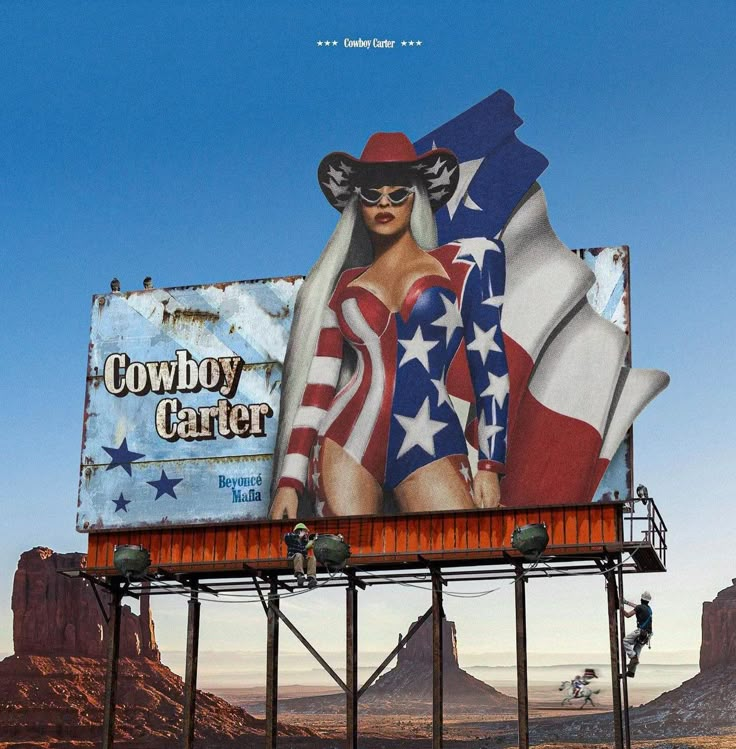

On her album, Beyoncé makes this very explicit from the cover: not only because of the horse—which seems to be the central theme of the trilogy—but also because of the presence of elements completely associated with country life, such as the boots, the hat, and the jackets, all of them elevated by a significant detail: the colors of the American flag, with an intensity that is now very easy to associate with the Trump campaign through satire.

What he sought to be

At this point, questioning the quality of Beyoncé’s performance on a record would practically be a waste of time: first, because of the vocal and interpretive talent she was born with; second, because of the caliber of collaborators she surrounds herself with; and last but not least, because of the nearly unlimited budget that allows her to record wherever, whenever, with patience and an attention to detail that few others can muster.

Therefore, by Beyoncé’s standards, successfully realizing her ideas is no longer an achievement but an obligation.

However, in addition to being a very finely crafted and polished album, Cowboy Carter is very entertaining. Which is a victory considering it’s an album of over an hour that explores genres that aren’t the most popular today.

And that victory is magnified by perhaps the album’s greatest virtue: the management and containment of emotions. Let’s remember that Beyoncé is coming off three atomic bombs ( Lemonade, The Carters, and Renaissance) that have marked her as a fast-paced and euphoric figure, so seeing her in this role not only reminds us of her eclecticism, but also expands her own range into more minimalist and solemn realms.

What ends up being

The problem with Cowboy Carter is that the distance between what he claims to be and what he actually ends up being is wide.

Because while it turned out to be a beautiful work to listen to, it doesn’t quite fulfill its mission of vindicating the African-American community within the history of Country.

In fact, in several passages it seems that she does exactly the opposite, since she constantly ends up alluding to the white canon of the genre: from the names with which she collaborates (Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Willie Nelson and Miley Cyrus) to the references she uses, in which through covers, samples and interpolations she feeds the already established perception of Country: “Jolene”, “Blackbird”, “Those Boots Are Made For Walking” among others.

A series of devices that are even bordering on the obvious,

and that don’t even give any sign of being there as an irony. And if anyone had the influence and credibility to bring other songs and other names to the table, it was Beyoncé.

But the focus should not be on what we would have liked to see presented, but on what is there:

In that aforementioned victory in performance, their harmonies – to give an example – have a vocal approach much closer to the Beach Boys and Bobby Gentry than to Charly Pride and Linda Martell.

So in the final conception of the album, more than a pedagogical route to reconstruct a cultural (and therefore, collective) origin of black Country, what Beyoncé achieved was a kind of personal revenge in which at the end of the road she has the arguments to say “I can play their game and even do it better than them.”

And even in the rigor of that white Country, the majority of the album is more of a work of contemporary acoustic Pop, very much in the tone of Taylor Swift’s Folklore or Mitski’s most recent album.

Which isn’t bad at all, but it doesn’t endorse what Beyoncé was going for. Or at least what she implied she was going for.

That’s true: under the less orthodox understanding of Country, Cowboy Carter could mean a new door for the genre in which, paradoxically to what was said a couple of paragraphs ago, the sonic diversity of African-American Music will have an ideal canvas to develop, something that would not be entirely new (a nod to Lil Nas X) but would establish a precedent for more black artists to become interested.

Read also: The 7 parts of write a review and how to write them